Gasometers: lost witnesses of Monaco’s industrial revolution

Three metal giants loomed large in the La Condamine district for a century. This is the story of a mini industrial revolution, at the crossroad of modernity and nostalgia, in a Principality in constant search of greatness.

There was a time when Monaco smelt of coal gas. A time when three cylindrical giants stood on the shores of the Mediterranean, silent witnesses to an energy revolution that was transforming Europe. Between 1866 and 1964, La Condamine’s gasometers provided lighting for the Principality, and accompanied its metamorphosis as a tourist destination, but nobody seemed to care when they vanished. We take a look back at the little-known saga of these energy giants.

The boldness of a principality in the making

The year is 1864. Lighting is being introduced to cities all over Europe. Paris, London and Berlin are discovering the advantages of gas lighting, a revolutionary coal-based technology that turns night into urban light. Night-time strolls are becoming more common, safety is improved and trade is flourishing. Monaco, still struggling to exist on the European map, grasps the stakes: to attract travellers, it needs to shine.

“At a time when everything in the Principality is being readied for gas lighting, our readers will be interested in a brief account of the establishment of this lighting system in Paris,” wrote the Journal Officiel on 16 July 1865. Behind the words lay an ambition: to make Monaco a testbed of modernity.

Waste treatment: Symbiose project abandoned, Government banks on new energy recovery facility

The Société des Bains de Mer was already shaping the Principality’s destiny at the time, and was entrusted with a sizeable task in 1863. “Its concession contract required it not only to supply gas to the government for lighting state-owned buildings, but also to supply gas to private individuals for their domestic needs,” explains Charlotte Lubert, SBM’s Heritage Manager. Its responsibility went far beyond just lighting: this was about building the energy foundations of a nation.

The first glimmers

The project began to take shape in June 1864. A gasworks was to be built at the foot of Fort Antoine, connected by “a sturdy pipe almost 400 metres long”* to the first gasometer at the foot of Avenue du Port. This enabled the industrial infrastructure to fit in with Monaco’s geography, its small footprint calling for ingenuity.

4 January 1866 is engraved in the history of Monegasque energy. On that day, Mr Marchessaux, whose name is cited in the Official Journal no. 0395 of 7 January 1866, lit the gaswork’s furnaces for the first time. A month later, in February, the official gas lighting inauguration transformed Monaco into a showcase of Mediterranean modernity.

Monaco was growing, its population increasing and its energy soaring. Demand quickly outstripped the capacity of the first gasometer. In 1872, and again in 1880, two new telescopic gasometers were built to “supply the gas burners at La Condamine and Les Moulins.”* The Principality became equipped methodically, with the discipline that underpins the necessary efficiency of small nations.

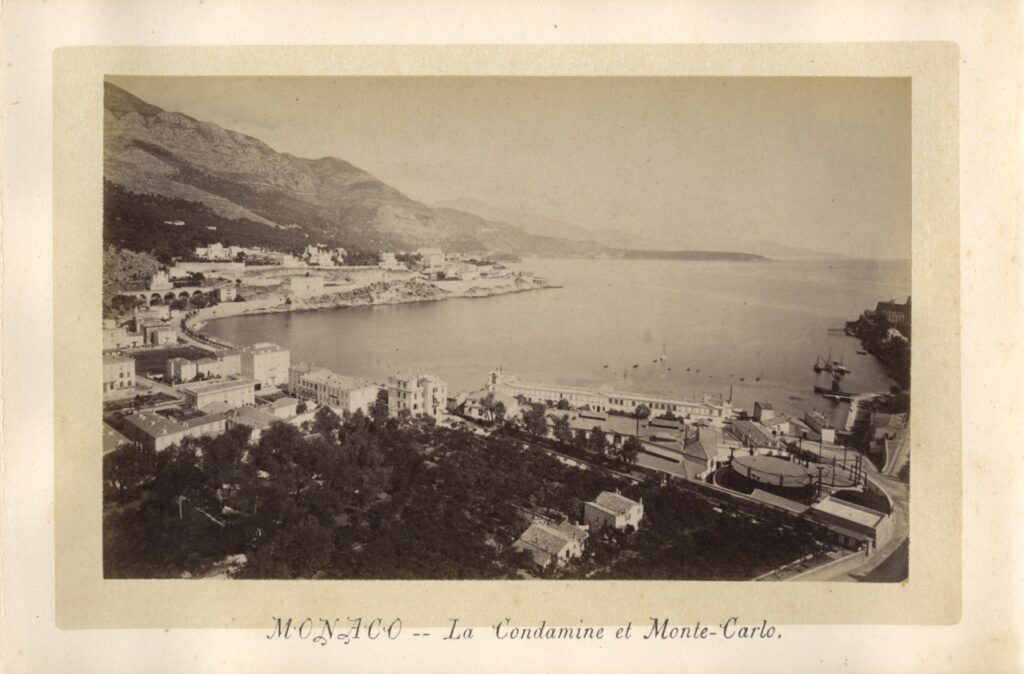

This photograph – taken in the early 1870s (circa 1872-1874) and kept in the archives of Monaco’s Audiovisual Institute – captures this pioneering era with the precision of a historical testimony. The global view of Monte-Carlo and La Condamine shows a landscape that is undergoing a transformation: in the centre, Port Hercule and its traditional maritime activity; on the left, the burgeoning district of Monte-Carlo with its Beau-Rivage hotel, a symbol of a nascent luxury tourism industry; higher up, the casino and its railway line, promising fortune and ease of access. Bottom right: the gasometers.

- * extracts from the book Monaco aux derniers temps de la marine à voiles (Monaco in the last days of Navy Sailing Ships), Claude Vaccarezza (2002)

Industrial boom

With a total capacity of 10,200 cubic metres, the metal giants, “painted in light colours to make them less obtrusive,” demonstrate a unique concern. Monaco was already exhibiting the aesthetic obsession that was to become its trademark. Industry, sure, but lovely. Modern, certainly, but harmonious. The gasometers later returned to their original greyish hue, as if the Principality had come to accept their utilitarian presence.

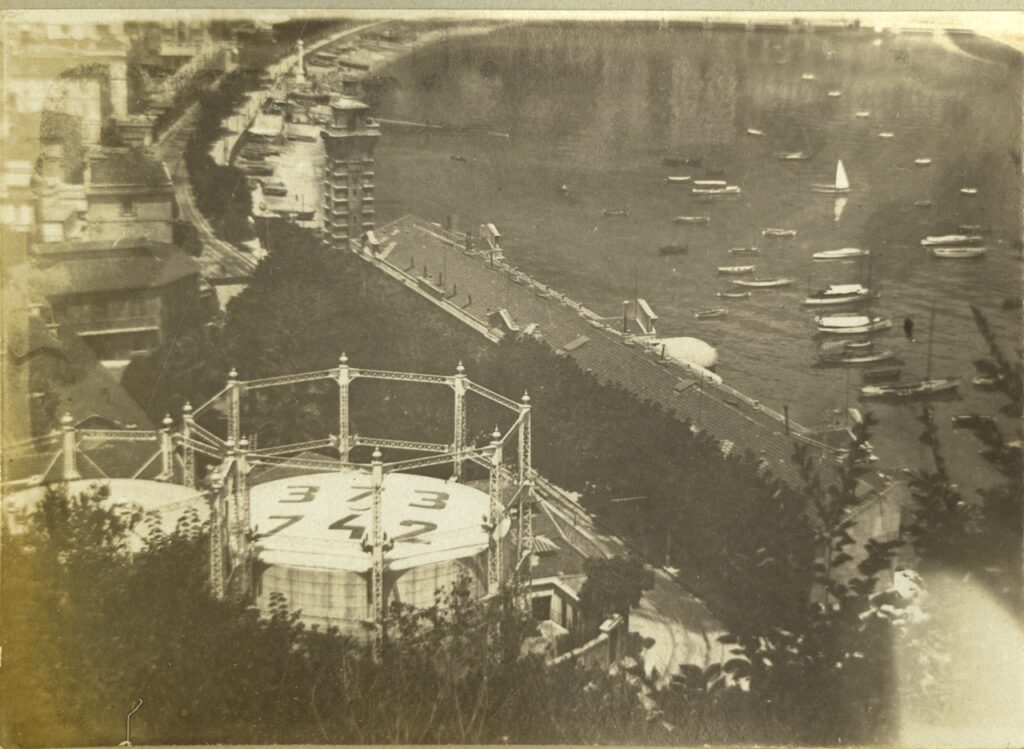

The 1910 photograph captures the height of this industrial era. The view from the Rocher overlooking La Condamine reveals a well-organised urban landscape. On the left, the gasometers bear the numbers “373 and 742”, indicating the quantity of gas stored there. In the distance, the monument presented by the Monegasque people to Prince Albert I to mark his jubilee is a reminder that this industrial modernity flourished during the reign of an enlightened monarchy.

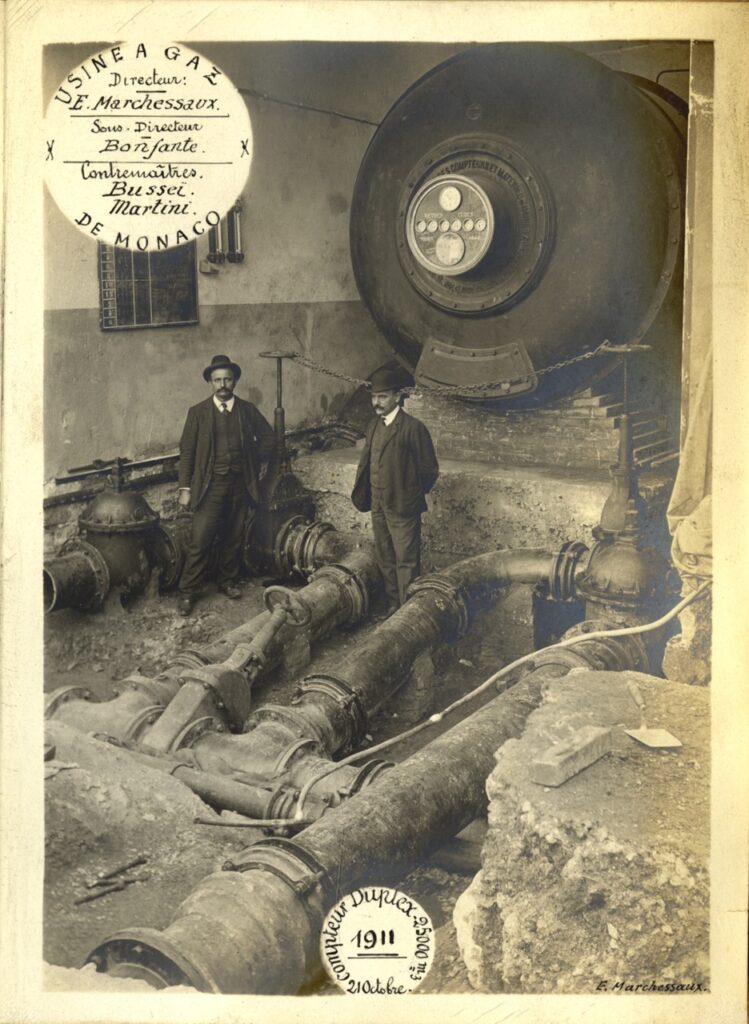

Behind the scenes of this well-oiled system, inside the gasworks, pipes carried the fluid to the gasometers before distribution to the town. The 1911 image also features foremen Bussier and Félix Martini; proudly posing in front of the pipes.

Brewing concerns

The Roaring Twenties put something of a spanner in the works. In November 1924, in the light of constant complaints, SBM asked Société du Gaz de Paris for expert advice. Henri Laurain, SGP’s Technical Director, became the consulting engineer with Gaz de Monaco. According to Charlotte Lubert, SBM’s heritage manager, in January 1925 he provided a detailed report of his findings in four chapters, a meticulous diagnosis of an energy system that was under strain.

In 1927, Henri Laurain delivered his verdict, recommending the construction of a new gasworks at Fontvieille, as well as major modifications to the existing Fort Antoine works. That same year, a photograph showed a glimpse of the infrastructure. The view from the sea shows how these facilities were part of the coastal landscape, but also their increasing isolation in a Principality that was already looking to other energy horizons. After some forty years of peaceful coexistence – the Société Monégasque d’Électricité (SME) was founded in 1890 – electricity was beginning to take over from gas, following the example of major European cities such as Paris.

At the same time, Monaco was taking a new view on urban space. In an unexpected twist, the gasometers became a landmark in the geography of emerging motor sport: in 1929, the first automobile Grand Prix made a circuit out of the Principality’s streets. The track included a hairpin turn known as the “Gasometer bend”.

A major turning point came on 1 October 1936. On that day, the SBM handed a number of services it had previously been responsible for, namely wastewater, water, gas, printing and roads, to the Monegasque Government. The State took control of its vital infrastructure, a sign of political and technical maturity.

Twilight hours for the giants

The Second World War accelerated these changes. In 1944, the gas infrastructure was seriously damaged, but quickly repaired by SMEG. Thew event was a catalyst for deeper consideration of the Principality’s energy future. In 1952, a tripartite agreement (the State, Gaz de France, Société Monégasque du Gaz) sealed the gasometers’ fate, as it planned the gradual phasing out of gas production locally. Monaco voluntarily entered an era of energy dependency, now importing town gas via Nice.

The closure of the gasworks in 1954 was a symbolic milestone. The gasometers lost their industrial purpose, becoming purely reservoirs in a delocalised energy system.

A final twist was immortalised in 1956, one last moment of glory. On 12 April 1956, at 9.30 am “Madame Grace Patricia Kelly, her parents and guests, having left New York on 4 April aboard the liner Constitution, arrived in Monaco harbour (…) On board the Deo Juvante II, with himself at the helm, H.S.H. the Sovereign Prince went to meet his fiancée,” reads the Journal Officiel on 16 April. On the south quay at Port Hercule, from a building under construction, we see the crowd awaiting the arrival of Grace Kelly from the United States, beneath the massive frames of the gasometers. There is symbolism in the image: the old industrial world contemplating the advent of Hollywood glamour, while American and Monegasque flags flutter in a sky full of promise.

The last photograph of the gasometers dates from 1961. The gasworks building was demolished four years previously, a victim of both urban and technological change. The debates at the National Council meeting on 31 December 1964 modestly referred to the budget for “moving the gasometers,” citing reasons to do with space for housing. A year to the day later, in 1965, Charles Bernasconi asked: “Is it on the former gasometer site that you are to erect this new building?” The sentence used in the minutes makes it clear: the gasometers were already a thing of the past.

Epilogue

Their only remaining trace is in the memory of F1 fans, with the iconic bend in the circuit. In 1972, Jean-Pierre Beltoise won the only victory of his career in the final race that included the ‘Gasometer bend’. The following year, the circuit was modified to take into account major development work in the harbour: the old bend was replaced by a new pit entrance and the current section that includes the Antony Noghès bend and the section in front of La Rascasse.

A Monaco train with a tragic end

What remains of the La Condamine gasometers? A name in automotive archives, a few yellowed photographs, the memory of a time when Monaco dared to be industrial. Thee metal giants accompanied the transformation of a fishing principality into a testbed for luxury tourism. They lit the first steps on the road to Monegasque modernity, before giving way to the demands of contemporary urban planning.

Their disappearance is a perfect illustration of Monegasque metamorphosis: knowing how to let go of the old without forgetting the boldness that inspired it, welcoming the new without losing our collective soul. The La Condamine gasometers, witnesses of a dream of industry and another of tourism, are a reminder that today’s Principality was built on more austere foundations that today’s glitter might suggest.